An Introduction To The Neuroscience Of Consciousness

Discover how the brain creates subjective experiences

Consciousness is arguably the biggest mystery of the universe.

It is about what it is like to be me, you, or another species. For some, it is about how matter becomes imagination (Tonini and Edelman, 1998). At its core, it is about subjective experiences.

This post serves as a friendly introduction to the topic.

I will focus on the neuroscience of consciousness, its philosophical background, how we study consciousness, and the most prominent theories.

Enjoy.

Before you read:

I’m not an expert on the topic. I have just read tons of papers about it and started to (indirectly) research it in birds.

Consciousness is a huge topic that can not be summarized in a single article. This is just a general overview.

You can find all the 30 references I used at the bottom and through this article.

Table of contents:

The Philosophical Problem.

How Neuroscientists Do Research On Consciousness?

2 Theories of Consciousness

Books Recommendations

1. The Philosophical Problem

For a long time, consciousness was only a topic for philosophers.

However, after the pioneering work by Crick & Koch (1990) (who suggested studying the neural correlates of consciousness), consciousness gained significant attention in the scientific community. Since then, many theories have been proposed (for a review, see Seth & Bayne, 2022).

Philosophy, its ideas, and its definitions shape how we do research.

In consciousness, this is notorious.

Here are the most important ones:

A. -isms

In “Being You: A New Science of Consciousness,” Anil Seth (2021) summarizes the -isms as:

Functionalism: consciousness depends on the functions performed by the brain, not on its physical structure.

Materialism: consciousness arises from physical processes in the brain.

Dualism: consciousness and physical reality are separate things.

Panpsychism: consciousness is a fundamental property of all matter.

Idealism: consciousness is the primary reality, and the physical world emerges from it.

Illusionism: Consciousness is an illusion; it doesn’t exist as we experience it.

B. The Hard and the Easy Problem(s)

Welcome to one of the most influential philosophical ideas.

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers (1995) argued that consciousness has two problems: the easy ones and the hard one. The easy(s) problem(s) relate to finding the neural substrates for conscious perception, memory, and other behaviors.

Of course, this problem is tricky.

So what’s the hard one? For Chalmers, it is explaining how the brain, a physical thing, creates a subjective experience. Nagel (1980) proposed a smart and popular thought experiment to understand the core of this problem:

What is it like to be a bat?

Bats echolocate.

Well, try to imagine how to do that. Close your eyes and make a sound. Imagine the sound waves traveling and hitting your coffee mug. Now, feel how those waves come back to you. Next, perceive what’s there (the coffee mug).

If you did this to answer the question, you are wrong.

Nagel argues that trying to imagine what the bat feels is incorrect. The correct answer is what the bat feels as a bat. That’s the hard problem of consciousness. For them, (as far as I know) impossible to solve.

Ironically, this problem has another one:

Take it by heart, and you fall into dualism, the idea that mind and brain are separate things.

Follow dualism, and you are giving up on a scientific explanation.

C. Phenomenological Consciousness vs Access Consciousness

Perhaps we should separate different kinds of consciousness.

That’s what Block (1995) suggested in his seminal paper. For him, access consciousness refers to the sensory information that becomes conscious. Phenomenal consciousness, on the other hand, is pure subjective experience.

The hard problem is explaining phenomenal consciousness.

The easy ones are related to access consciousness.

D. Illusionism

These people deny entirely the hard problem.

For them, what we experience as “consciousness” is not what it seems. They argue that subjective experiences are nothing mysterious; they are just illusions our brains create (Frankish, 2016).

Do you feel mad about it?

I did. It sounds like they deny my subjective experiences related to my feelings for my wife or anything. But this is not what they mean. Illusionists argue that your subjective experiences ARE real.

However, they are a product of your brain.

What we perceive as conscious experiences is the brain’s “user-friendly” way of interpreting complex information. Phenomenal consciousness is illusory. Because qualitivate experiences are just brain processes.

Our minds create the illusion of a mysterious experience.

That’s why it is an illusion.

Influential minds from this view are:

Daniel Dennett.

Keith Frankish.

2. How Neuroscientists Do Research On Consciousness?

Well, this depends on how they understand it.

For example, illusionists who argue that phenomenological consciousness is an illusion focus on access consciousness. Then, they design (in its basic form) experiments in which participants can consciously perceive stimuli.

This is not the case for the other team interested in phenomenological consciousness.

For them, experiments should be designed to study pure subjective experiences.

Here are some classic examples.

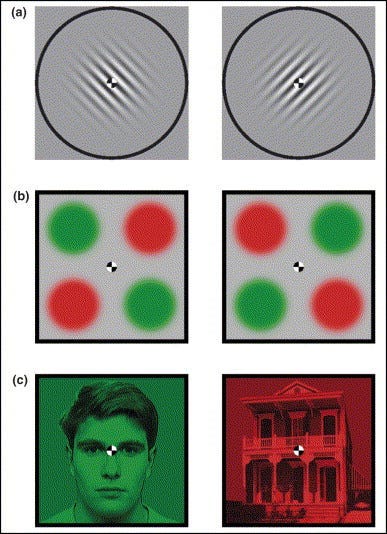

1. Binocular Rivalry

This occurs when each eye is shown a different image simultaneously.

When doing so, the brain alternates between them, making perception switch from one image to the other. For example, you don't perceive a mix of both when seeing a blue circle and an orange square.

You might see one of them switching perceptions back and forth.

This simple method shows how the brain determines what we consciously see. By measuring the brain activity when participants are presented with this kind of stimuli, we can study the correlates of conscious perception.

However, this method focuses on access consciousness instead of pure subjective experiences.

2. Priming

Priming is a phenomenon where exposure to one stimulus influences the response to another.

Often without conscious awareness.

Using priming, neuroscientists can explore the “unconscious” information processing and delineate the boundary between conscious and unconscious perception.

If I present an image briefly, you will probably not see it.

But if I present it to you a bit longer, you may see it.

This is how we can delineate the boundary of conscious perception. Priming shows that not all cognitive processes are available to conscious experience.

And even when we don’t perceive something consciously, there’s much unconscious perception going on in our brains.

This is a very different idea from what Freud proposed originally.

3. Dreams

Dreams have always fascinated humans.

Sleep allows us to monitor how we go from awareness to non-consciousness. In the middle of the night, dreams, pure subjective experiences, arise from the sleeping brain.

This is why they are relevant to the science of consciousness.

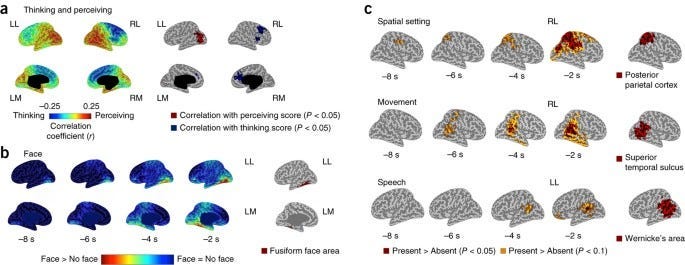

In a fantastic paper published in Nature, Siclari et al. (2017) used a high-definition electroencephalogram (hd-EEG) to predict the content of dreams.

They found that a posterior cortical “hot zone” was significantly activated when participants reported dreams.

Using this and other brain areas, they could predict if someone had a dream experience AND its content. For example, if this hot zone and fusiform face area were activated, researchers could infer that the [participant was dreaming about faces.

Blowminding.

4. Other methods:

The mirror test (for a review, see Boyle, 2017).

Psychedelics (for a review, see Yaden et al., 2021).

Metacognition (for a review, see Fleming, 2023).

Illusions (see Constantini & Haggard, 2007 for the “Rubber Hand Illusion” as an example)

Way more.

2 Theories

This is where all things mess out.

Ironically, consciousness arguments are subjective. By this, I mean that people are (very) biased in how they think consciousness works. For example, some argue qualia don’t exist; consciousness is like energy distributed in the universe: spiritual things, gods, etc.

I even read people (not scientists) saying that neurons do not exist.

Anyways.

In the last decades, two theories have become the most cited ones:

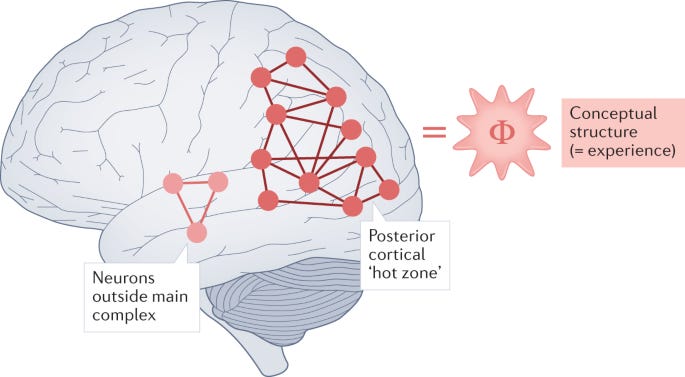

A. Integrated Information Theory (IIT)

This is a unique approach to studying the hard problem of consciousness.

First proposed by Giulio Tononi in “An Information Integration Theory of Consciousness” (Tononi, 2004), IIT defines consciousness as integrated information.

He proposes a way to measure and quantify consciousness with Phi.

IIT aims to explain phenomenal consciousness in physical terms. Rather than starting from behavioral, functional, or neural correlates, IIT tackles experience first.

They argue that the existence of an experience is irrefutable.

From this, they propose five axioms of phenomenal existence: every experience is for the experiencer (intrinsicality), specific (information), unitary (integration), definite (exclusion), and structured (composition) (Albantakis, 2023).

Although attractive, his theory has been largely criticized.

Its main problem is Phi. In his book “In Consciousness We Trust,” Lau (2021) makes fun of this by saying that a teacup could be exactly 0.0000000247% as conscious as your cat. For a fair critique, I highly recommend reading Aronson’s blog:

https://scottaaronson.blog/?p=1823

or Lau’s book.

Anyways.

Finally, Tononi and his colleagues argue that the brain region with higher Phi is a posterior cortical “hot zone” (the one found by Siclari et al., 2017):

It is not hard to see why many scientists don’t take this theory seriously.

It falls into panpsychism.

For this reason, recently, a letter signed by many neuroscientists claimed that IIT should be labeled as pseudoscience (auch!). However, this was finally retracted.

Yeah, it was excessive.

One last point. IIT criticisms led Tononi and his team to publish updates (or upgrades) of his theory. Now, we have IIT 1.0, IIT 2.0, IIT 3.0, and IIT 4.0—like an Evangelion movie.

In summary, at its core, Phi can not be falsified.

It suffers from theoretical and practical issues.

However, that a Theory can not be falsified or proved doesn’t mean it is incorrect. More research and redefinitions are needed to understand consciousness.

In the meantime, Tononi and his team obtained exciting results and predictions relevant to the science of consciousness, such as the 2017 paper by Siclari et al. (for more results, see Koch et al., 2016).

B. Global Neuronal Workspace Theory

This is a strong cognitive neuroscience theory.

Baars proposed it (1997, 2005), which Dehaene & Naccache (2001) complimented. In a nutshell, for them, consciousness happens when information becomes available to the brain's global workspace.

In contrast with IIT, GNWT has vast and robust evidence to support it (Mashour et al., 2020).

However, philosophers and some scientists don’t like it. GNWT studies access consciousness. The hard problem is not a problem for them (Dehaene, 2014). Why? Well, because it is an illusion.

They argue the only problem is explaining access consciousness.

This is why many argue it is an incomplete theory.

Anyways. This is how their theory works.

They argue the brain has modular processors that unconsciously handle different types of information. These work in parallel, performing tasks without conscious awareness.

Consciousness arises when information from these modules is broadcast widely across the brain.

This region, which has a network of interconnected neurons, is what they define as the global workspace, which includes cortical areas, particularly the pre-frontal cortex.

So when a specific stimulus is strong enough to capture attention, it amplifies and gains access to the global workspace (think about it as a router).

Once there, it becomes consciously perceived.

To learn more about this theory, read this paper.

C. More Theories

Higher Order Theory (HOT) (LeDoux & Brown, 2017).

Prefrontal perceptual reality monitoring (PRM) (Lau, 2021) (affiliate link).

Beast Machine Theory (Seth & Tsakiris, 2018).

For a review of 22 theories, see Seth & Bayne, 2022.

4. Book Recommendations

If you come this far, here are some book recommendations:

“Being You: A New Science of Consciousness” by Anil Seth (affiliate link).

“Consciousness Explained” by Daniel Dennett (affiliate link).

“The Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self” by Thomas Metzinger (affiliate link).

“Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts” by Stanislas Dehaene (affiliate link).

“A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination” by Giulio Tononi and Gerald Edelman (affiliate link).

“In consciousness we trust: The cognitive neuroscience of subjective experience” by Hakwan Lau (affiliate link).

Summarizing consciousness in one article is not fair.

My goal was to provide a friendly introduction to the topic. Philosophical ideas and consciousness theories are violently summarized here. If you are interested, I highly encourage you to read my cited papers.

I hope you enjoy reading it.

Would you like to read more about it? :) let me know in the comments!

The brain is fascinating.

It’s the origin of everything we experience—our emotions, perceptions, consciousness, and behaviors. Every thought and action is driven by complex biological algorithms that evolved over millennia, shaping our nervous systems into finely tuned machines.

Ultimately, our brains are what make us human.

The more we understand it, the closer we understand ourselves and other life beings.

Until the next time,

Axel

References

Albantakis, L., Barbosa, L., Findlay, G., Grasso, M., Haun, A. M., Marshall, W., … & Tononi, G. (2023). Integrated information theory (IIT) 4.0: formulating the properties of phenomenal existence in physical terms. PLoS computational biology, 19(10), e1011465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011465

Baars, B. J. (1997). In the theatre of consciousness. Global workspace theory, a rigorous scientific theory of consciousness. Journal of consciousness Studies, 4(4), 292–309.

Baars, B. J. (2004). Global workspace theory of consciousness: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of human experience. Progress in Brain Research, 150, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50004-9

Balduzzi, D., & Tononi, G. (2009). Qualia: the geometry of integrated information. PLoS computational biology, 5(8), e1000462. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000462

Block, N. (1995). On a confusion about a function of consciousness. Behavioral and brain sciences, 18(2), 227–247.

Boyle, A. (2018). Mirror Self-Recognition and Self-Identification. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 97(2), 284–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12370

Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of consciousness studies, 2(3), 200–219.

Costantini, M., & Haggard, P. (2007). The rubber hand illusion: Sensitivity and reference frame for body ownership. Consciousness and Cognition, 16(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2007.01.001

Crick, F., & Koch, C. (1990, January). Towards a neurobiological theory of consciousness. In Seminars in the Neurosciences (Vol. 2, №263–275, p. 203).

David B Yaden, Matthew W Johnson, Roland R Griffiths, Manoj K Doss, Albert Garcia-Romeu, Sandeep Nayak, Natalie Gukasyan, Brian N Mathur, Frederick S Barrett, Psychedelics and Consciousness: Distinctions, Demarcations, and Opportunities, International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, Volume 24, Issue 8, August 2021, Pages 615–623, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyab026

Dehaene, S. (2014). Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts. Viking.

Dehaene, S., & Naccache, L. (2001). Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: Basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition, 79(1–2), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00123-2

Dennett, D. C., & Dennett, D. C. (1993). Consciousness explained. Penguin UK.

Edelman, G. M., & Tononi, G. (2013). Consciousness: How matter becomes imagination. Penguin UK.

Fleming, S. M. (2024). Metacognition and confidence: A review and synthesis. Annual Review of Psychology, 75(1), 241–268. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-022423-032425

Frankish, K. (2016). Illusionism as a theory of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 23(11–12), 11–39.

Geukes, S., Huster, R. J., Wollbrink, A., Junghöfer, M., Zwitserlood, P., & Dobel, C. (2013). A Large N400 but No BOLD Effect — Comparing Source Activations of Semantic Priming in Simultaneous EEG-fMRI. PLOS ONE, 8(12), e84029. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084029

Koch, C., Massimini, M., Boly, M. et al. Neural correlates of consciousness: progress and problems. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 307–321 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.22

Lau, H. (2022). In consciousness we trust: The cognitive neuroscience of subjective experience. Oxford University Press.

LeDoux, J. E., & Brown, R. (2017). A higher-order theory of emotional consciousness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(10), E2016-E2025. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619316114

Mashour, G. A., Roelfsema, P., Changeux, J. P., & Dehaene, S. (2020). Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Neuron, 105(5), 776–798. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.026

Metzinger, T. (2010). The ego tunnel: The science of the mind and the myth of the self (Vol. 16). ReadHowYouWant. com.

Nagel, Thomas. “11. What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”. Volume I Readings in Philosophy of Psychology, Volume I, edited by Ned Block, Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, 1980, pp. 159–168. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674594623.c15

Oizumi, M., Albantakis, L., & Tononi, G. (2014). From the phenomenology to the mechanisms of consciousness: integrated information theory 3.0. PLoS computational biology, 10(5), e1003588. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003588

Seth, A. (2021). Being you: A new science of consciousness. Penguin.

Seth, A. K., & Bayne, T. (2022). Theories of consciousness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 23(7), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-022-00587-4

Seth, A. K., & Tsakiris, M. (2018). Being a beast machine: The somatic basis of selfhood. Trends in cognitive sciences, 22(11), 969–981. 10.1016/j.tics.2018.08.008

Siclari, F., Baird, B., Perogamvros, L., Bernardi, G., LaRocque, J. J., Riedner, B., Boly, M., Postle, B. R., & Tononi, G. (2017). The neural correlates of dreaming. Nature Neuroscience, 20(6), 872–878. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4545

Tononi, G. An information integration theory of consciousness. BMC Neurosci 5, 42 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-5-42

Tong, F., Meng, M., & Blake, R. (2006). Neural bases of binocular rivalry. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(11), 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.09.003

Note: I added affiliative links for the book recommendations, so I may earn a small commission if you buy them through my links at no extra cost.